- Home

- Canna-culture

- A Century of Prohibition

A Century of Prohibition

Why Cannabis Still Isn’t Legal in the U.S. From 1925 to 2025: How fear, racism, and greed made cannabis illegal… and still keep it that way.

Table of contents

You’d think after 100 years, we’d be past this.

You can walk into a dispensary in over half the country right now and legally buy cannabis flower, pre-rolls, concentrates, edibles, the works. And yet, on the federal level, cannabis is still classified as a Schedule I drug. Still treated like heroin. Still considered dangerous, addictive, and medically useless by the same government that holds patents on its therapeutic uses.

So the obvious question is: Why?

Why is cannabis still federally illegal?

To answer that, we’ve got to rewind the clock. Not just to the 1970s and Nixon’s War on Drugs, but all the way back to 1925. That was the year cannabis first landed in the crosshairs of international drug policy. And once that first domino fell, it set off a chain of fear-based laws, racially charged crackdowns, and economic sabotage that still shapes our laws today.

Act I: The Setup (1925–1937)

Most people would say that the US prohibition of cannabis started 88 years ago, with the introduction of the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act. But that was just the true “nail that sealed the coffin”. The ‘setup’ for that nail actually happened 100 years ago.

The First Ban: 1925 and the Global Trigger

Cannabis prohibition didn’t start in the United States. It started in Europe, during a quiet backroom session of the 1925 Geneva Opium Convention. This was the first time cannabis (referred to back then as "Indian hemp") was placed under international drug control. The push didn’t come from science. It came from colonial powers like Egypt and South Africa, who argued that cannabis made native populations unproductive, unruly, and morally degenerate. It was a colonial and moral panic, not a medical one.

The United States wasn’t a leading voice in that moment. But they were listening. And they took notes.

The American Blueprint: Racism, Fear, and Quiet Profit

Picture from the Mexican Revolution (Britannica)

Picture from the Mexican Revolution (Britannica)

Back home, cannabis was already showing up on the radar of local lawmakers. By the early 1900s, Mexican refugees were entering the United States in large numbers, fleeing the violence and chaos of the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920). Many brought with them a long cultural tradition of consuming cannabis, called "marihuana" in Mexican Spanish.

As these communities settled in border states like Texas, New Mexico, and California, lawmakers responded with bans. Not because of what cannabis did, but because of who was consuming it. Police and politicians tied the plant to Mexican immigrants and to Black jazz musicians. White newspapers ran wild with sensational stories of cannabis-fueled violence, moral decay, and interracial relationships.

By 1933, 29 states had banned cannabis. By the mid-1930s, that number had climbed to nearly every state in the country. But racial fear wasn’t the only force driving those bans. There was money involved, too.

Enter the Tycoons: Mellon, Hearst, and Du Pont

Behind the scenes, a trio of powerful businessmen was lining things up for a full-scale prohibition.

Andrew Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury, was one of the richest men in America. He had investments in Gulf Oil and was a major backer of DuPont, a company that had just started manufacturing synthetic materials like nylon.

W.R. Hearst, the media mogul, had deep stakes in timber and paper. Hemp-based paper was cheaper and faster to produce, and it posed a direct threat to his empire.

Lammot du Pont II, the industrialist behind DuPont, saw hemp as competition to his new line of synthetic products.

Hemp was easy to grow, renewable, and incredibly versatile. It could be turned into paper, textiles, rope, biofuel, and even plastics.

That made it a major threat to the petroleum, chemical, and timber industries. Exactly the types of industries these tycoons were heavily invested in. But instead of competing fairly, these men backed prohibition as a way to kill off the competition by using their money and political influence to support the laws and bureaucrats that would take hemp off the playing field.

Sounds familiar, doesn't it?

The Enforcer: Harry J. Anslinger and the FBN

Enter Harry Anslinger, Mellon’s nephew-in-law. In 1930, Mellon appointed him as head of the newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Alcohol prohibition was winding down, and the FBN needed a new target. Anslinger gave them one.

He launched a national campaign to turn cannabis into public enemy number one. He didn’t rely on data. He relied on fear. He published sensationalist stories in Hearst’s papers. He tied cannabis to crime, insanity, and racial panic. He claimed it made men violent and women promiscuous. And he used quotes like:

There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, result from marijuana use.

Anslinger’s language wasn’t coded. It was openly racist, openly political, and widely broadcast. With Mellon, Du Pont, and Hearst backing the effort, prohibition moved quickly.

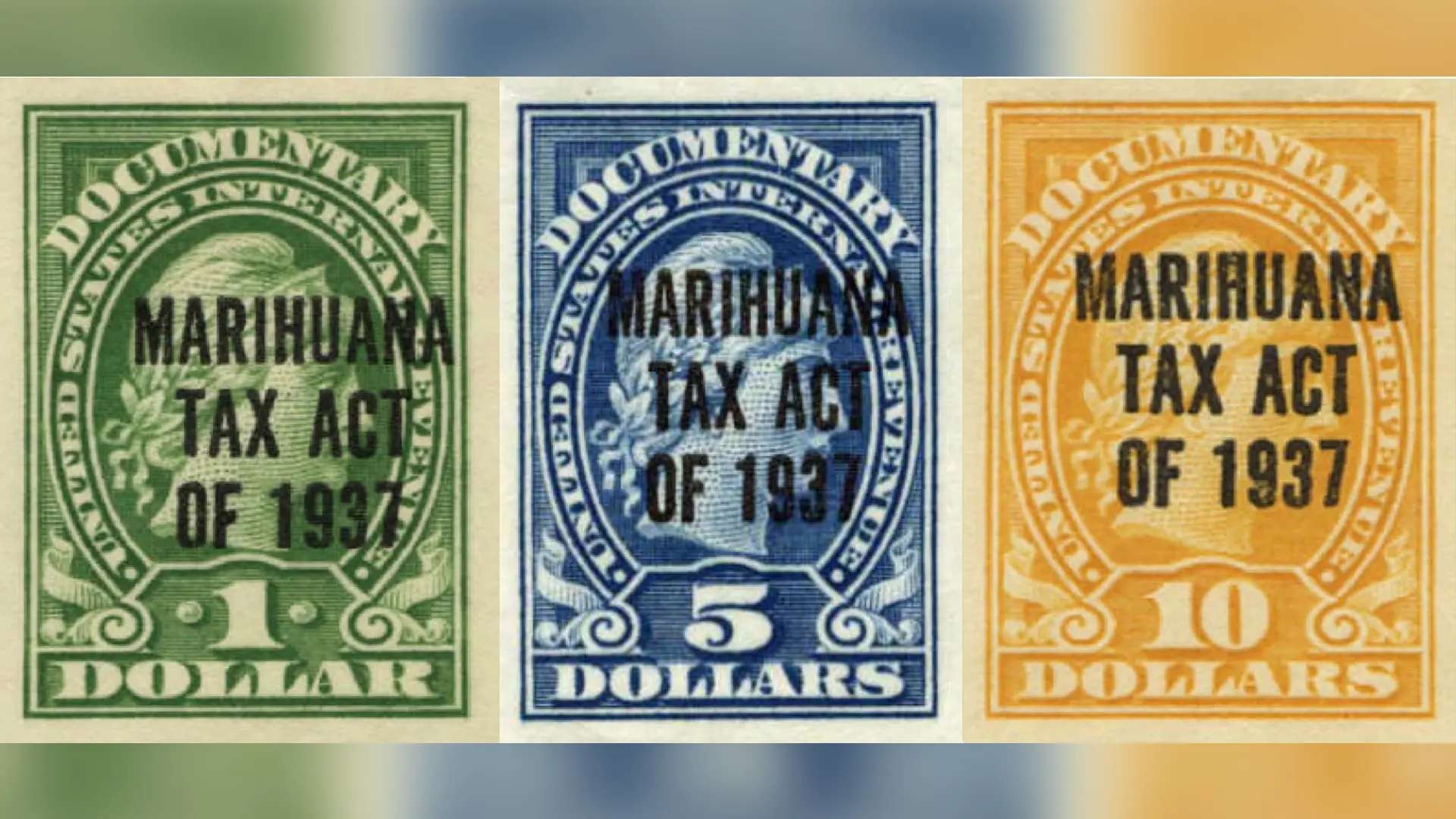

The Nail in the Coffin: The Marihuana Tax Act (1937)

In 1937, Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act. On paper, it didn’t ban cannabis—it just required anyone dealing with it to register and pay a tax. But the process was so restrictive, the effect was the same: criminalization by red tape.

The law gave federal agents broad power to target anyone involved with cannabis. It crushed the hemp industry almost overnight and solidified cannabis as contraband in the eyes of the public.

Like the bans before it, this law wasn’t about health or safety. It was about power, control, and protecting profits.

And it worked.

Our Bestsellers

Act II: Criminal by Design (1937–1970)

Governments need laws to crack down on undesirable elements. This is a given. Laws are tools of destruction as much as they are tools for good. One such tool was about to show which way it was going to swing.

From Taboo to Felony

After the Marihuana Tax Act passed in 1937, the shift wasn’t slow or subtle. Federal agents started making arrests almost immediately. Cannabis had gone from being an ingredient in common medicines and a staple industrial crop to a legal trapdoor. Anyone without a tax stamp (which the government rarely issued) was suddenly a criminal.

Enforcement hit hardest in immigrant and Black communities. Small-time growers, musicians, herbalists, and even doctors were caught in the net. The plant wasn’t just frowned upon anymore. It was criminalized.

And that was exactly the point.

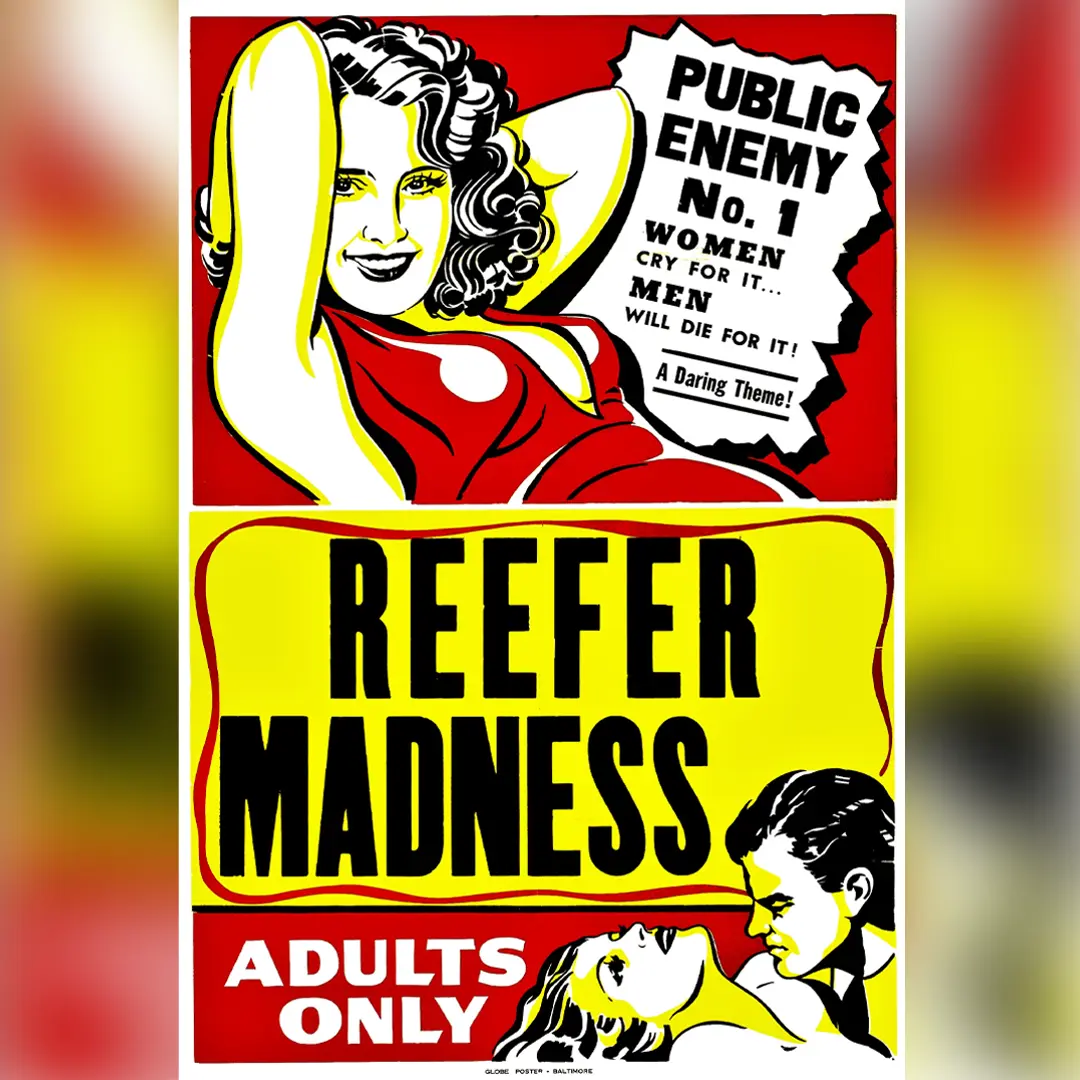

A Poster Child for Panic

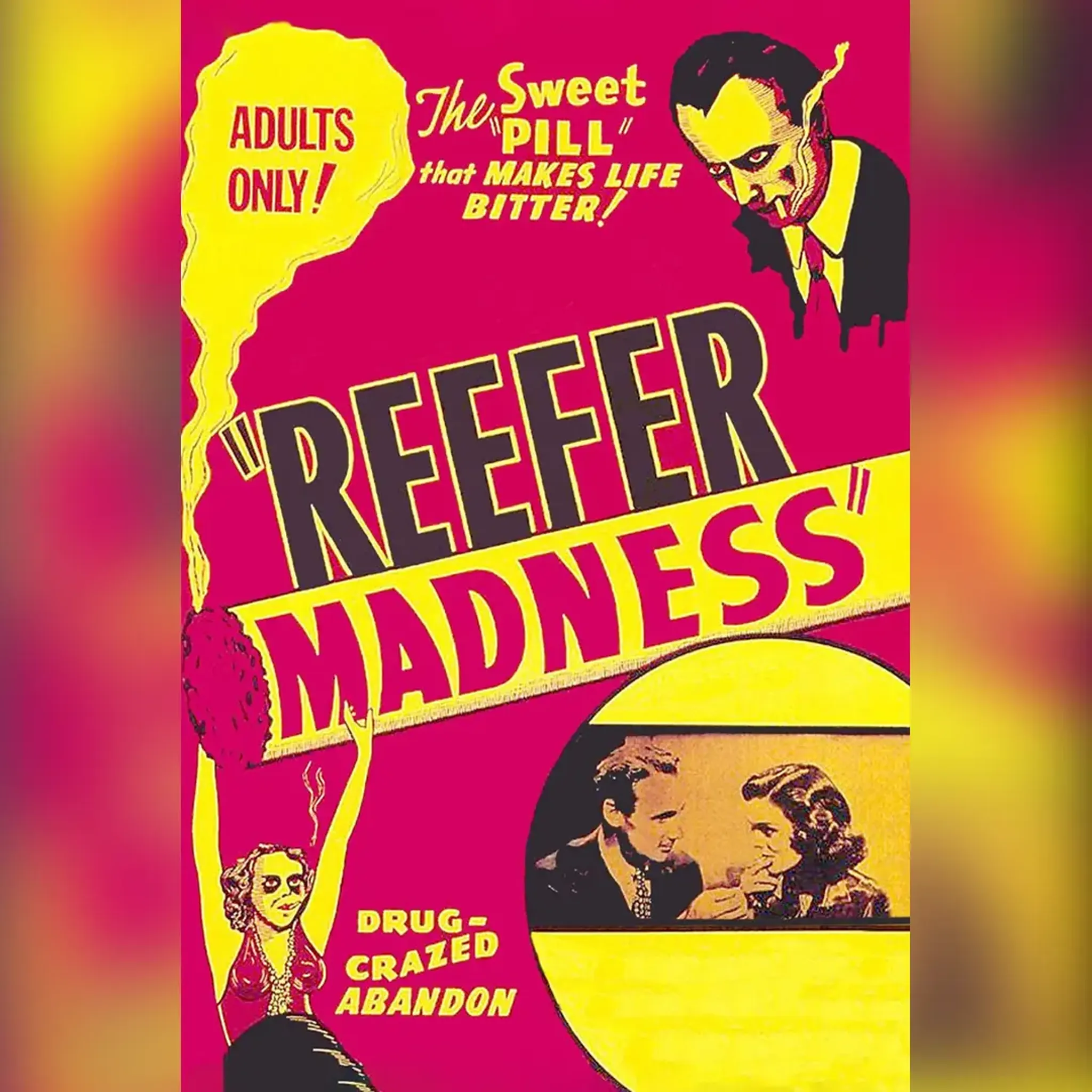

Harry Anslinger spent the next two decades pumping the public with fear. One of the most infamous propaganda pieces of the era was the 1936 film Reefer Madness, which portrayed cannabis as a direct line to insanity, murder, and moral collapse.

It was cartoonish. But it worked.

The Lockdown: Controlled Substances Act of 1970

By the late 1960s, cannabis wasn’t just a political issue. It was a cultural one. The plant had become a symbol associated with the antiwar movement, civil rights activism, and a younger generation rejecting traditional authority.

President Richard Nixon saw an opportunity. In 1970, his administration passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA), a sweeping federal law that placed drugs into categories, or "schedules," based on perceived medical value and risk.

Cannabis was dumped into Schedule I (the same category as heroin) reserved for substances deemed to have a high potential for abuse, no accepted medical use, and no safety under medical supervision.

This wasn’t based on research. In fact, Nixon ignored the findings of his own commission, which had recommended decriminalization. The CSA gave the federal government total control over cannabis and provided a scientific-looking justification for keeping it illegal.

It made the ban permanent, national, and a lot harder to undo.

They Said the Quiet Part Out Loud

Nixon’s motives weren’t a mystery—he recorded them. His aide, John Ehrlichman, later admitted:

The Nixon campaign... had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people... We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either... but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin... we could disrupt those communities.

Act III: Legal But Not Free (1980–2025)

“Often, things need to get worse before they get better”. The next four decades would show how true that idiom was (and still is). As the War on Drugs intensified and anti-drug laws became tools of mass incarceration, there was light at the end of the tunnel. A dim light, still far away, but a light nonetheless.

Before Legalization, There Was Lockup

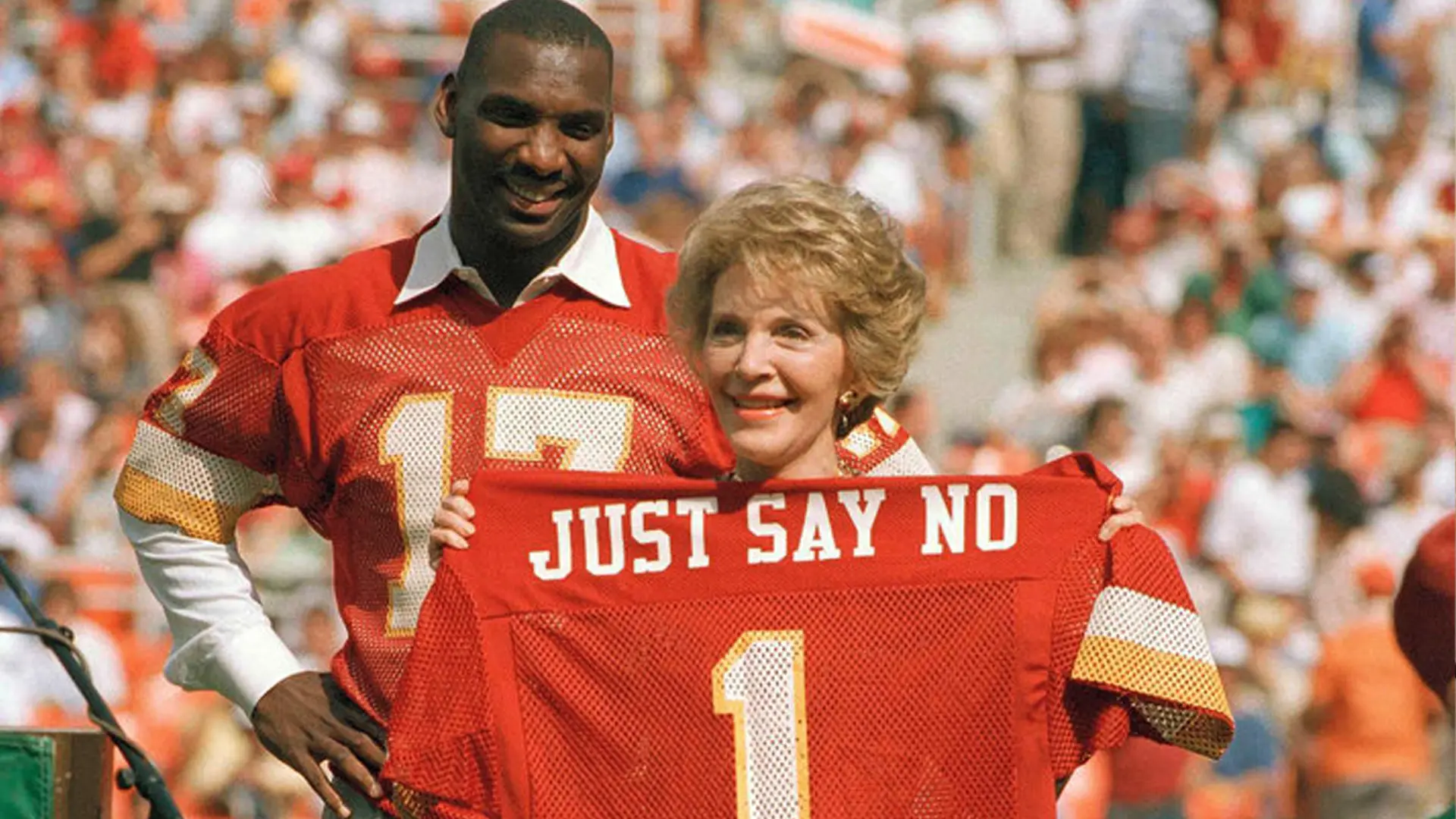

Before legalization gained traction, the War on Drugs reached its peak during the 1980s and 1990s. Under President Reagan, harsh mandatory minimums and “Just Say No” messaging fueled mass incarceration. Cannabis may not have been the primary focus, but thousands were arrested and jailed for possession alone, often with long sentences.

Then came President Clinton’s 1994 crime bill, which poured billions into policing and prisons. Arrests for cannabis surged, and communities of color bore the brunt of it.

These policies didn’t disappear when states started legalizing; they left a legacy that still shapes who gets to participate in the legal market today.

The First Cracks in the Wall, But The Wall Still Stands

In 1996, California passed Proposition 215, legalizing medical cannabis and setting off a slow-moving wave of state reforms. Over the next decade, other states followed: Oregon, Colorado, and Washington. It looked like change was finally happening.

But federally? Nothing changed. Cannabis stayed a Schedule I substance, and legal growers and dispensaries were still vulnerable to federal raids. People assumed medical laws meant safety, but the government kept the power to shut everything down.

Green Rush, Red Tape

By 2012, Colorado and Washington had legalized adult-use cannabis. Legalization picked up speed across the country. Cannabis became a billion-dollar industry almost overnight.

But legalization didn’t mean freedom.

The federal ban stayed intact, which meant cannabis businesses still couldn’t access traditional banking, were burdened by punitive taxes under IRS Code 280E, and were blocked from operating across state lines, even between two legal markets.

And while big investors flooded the market, legacy growers and small operators were buried under absurd regulations, impossible licensing processes, and sky-high compliance costs. Many of the people who risked everything to keep cannabis culture alive were now locked out of the legal game.

Legal, Stalled, and Still Under Threat

Despite public support and state-level wins, Congress keeps stalling on real reform. The SAFE Banking Act, MORE Act, and other federal efforts either die in committee or pass the House only to stall in the Senate.

And now, the 2025 Farm Bill threatens to redefine hemp as any plant containing more than 0.3% total THC, not just Δ9-THC. That change would criminalize a massive part of the hemp supply chain, and drag more growers back into legal limbo.

At the same time, the federal government pushes for rescheduling, not descheduling. That would hand control of cannabis to pharmaceutical companies and keep everyone else boxed out by FDA-style restrictions.

The War on Drugs didn’t end. It evolved.

Legal in Theory, Controlled in Practice

Today, cannabis is legal in most states. But arrests haven’t stopped. In 2023 alone, it’s estimated that over 220,000 people were arrested for cannabis-related offenses in the U.S. An estimated 84% of these arrests were for simple possession.

Many of the promises of legalization (equity, opportunity, justice) still haven’t been fulfilled. The same government that once hunted cannabis now wants to tax, regulate, and license it into submission.

If you have money, a law degree, and a clean record, the door might be open. If you’re a legacy grower, a small-scale farmer, or someone who built this culture during prohibition? You’re still being locked out.

Cannabis may be legal.

But it still isn’t free.

Conclusion: Grow Your Own, While You Still Can

After a hundred years of prohibition, it might feel like cannabis finally won. It’s on shelves. It’s in the headlines. It’s in your neighbor’s garden. But don’t mistake legality for stability. The war never really ended, it just evolved. And the systems that built it? Still standing.

Across the country, small dispensaries are closing their doors. Growers—both craft-scale and commercial—are being taxed, regulated, and priced out of the market they helped build. Between IRS codes like 280E, zoning crackdowns, oversupply crashes, and endless compliance costs, the legal industry is becoming less sustainable by the day.

And for those who prefer to grow at home? Don’t get too comfortable. The 2018 Farm Bill quietly opened the door for legal cannabis seed sales across state lines. But now that the bill is being rewritten. If the new 2025 Farm Bill redefines hemp to include total THC, it could instantly criminalize the seeds that home growers rely on. You might still be “allowed” to grow cannabis, but good luck getting your hands on seeds.

So what do we do with all this?

We grow anyway.

Because growing your own cannabis is the one piece of this plant’s story they haven’t managed to fully control, yet. It’s affordable, empowering, and resilient. It’s how you take something back. It’s how you stop waiting on politicians and policies and corporations to give you permission.

Grow your own. Because the plant was never the problem. The system was.

Herbert M. Green, signing off

Herbert M Green

As ILGM’s Head of Cultivation and Education, Herbert M. Green has only one mission: making growing cannabis easy and accessible for all.

Continue Reading

You might also find these interesting.